Historical Events

Research and collection by BlueArt.ch

Battle of Cape St Vincent

An important battle during the French Napoleonic Wars...

Battle of Santa Cruz de Tenerife

On 14 July Nelson sailed for the Canaries aboard his flagship HMS Theseus...

Battle of the Nile

An invasion of Egypt in order to constrict Britain’s trade routes...

Battle of Peninsular

A military conflict between France and Spain and its allies...

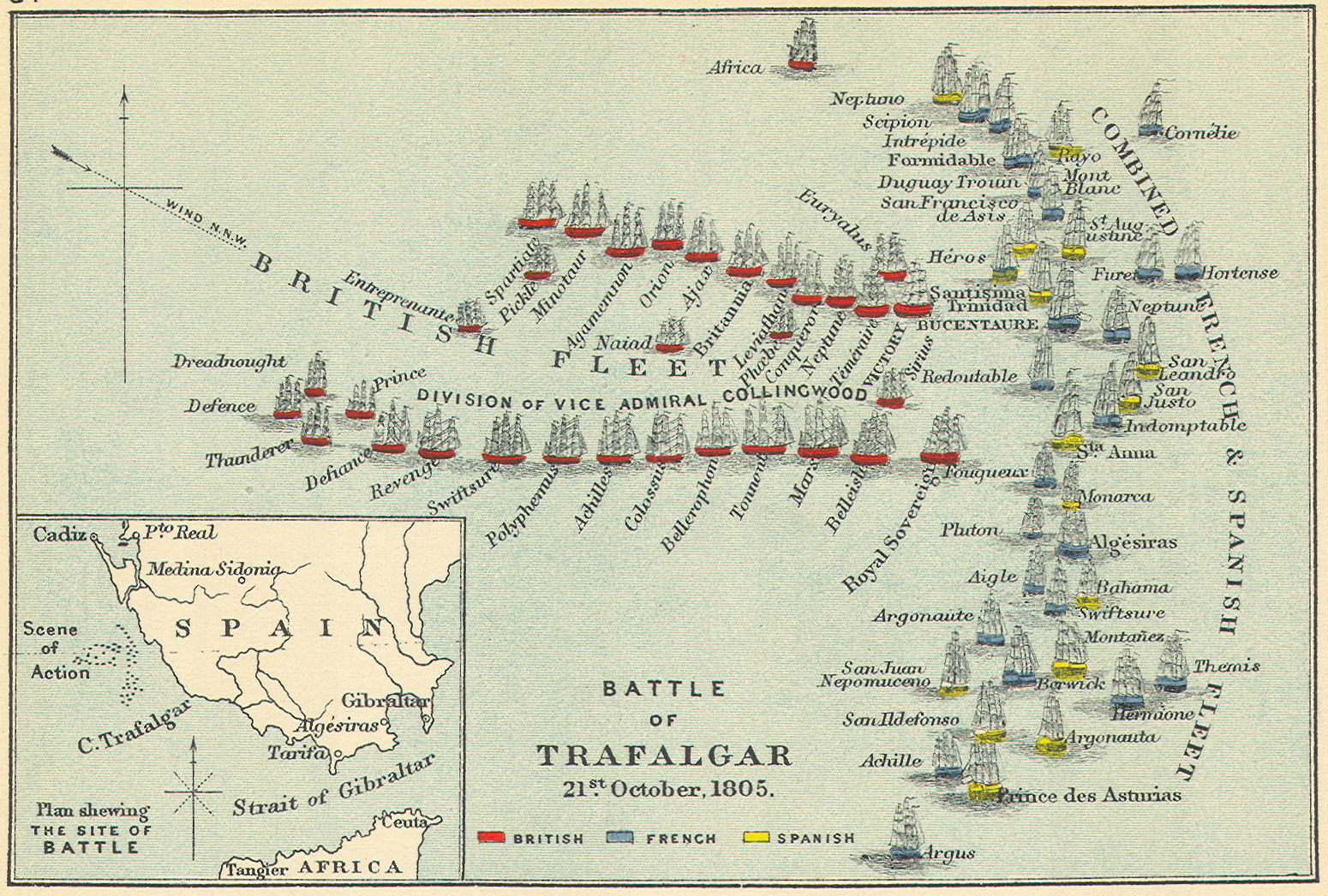

In one of the most decisive naval battles in history, a British fleet under Admiral Lord Nelson defeated a combined French and Spanish fleet at the Battle of Trafalgar, fought off the coast of Spain…

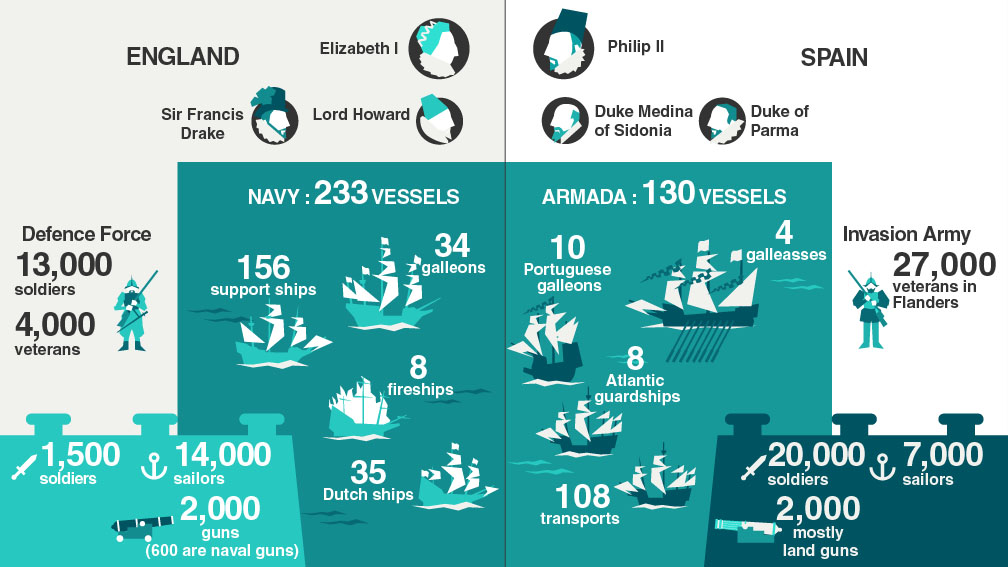

The Spanish Navy (Spanish: Armada Española) is the maritime branch of the Spanish Armed Forces and one of the oldest active naval forces in the world. It was an enormous 130-ship naval fleet…

Galleon Ships

The galleons were first used by the Spaniards as armed carriers...

In one of the most decisive naval battles in history, a British fleet under Admiral Lord Nelson defeated a combined French and Spanish fleet at the Battle of Trafalgar, fought off the coast of Spain.

In one of the most decisive naval battles in history, a British fleet under Admiral Lord Nelson defeated a combined French and Spanish fleet at the Battle of Trafalgar, fought off the coast of Spain.

At sea, the Royal Navy consistently thwarted Napoleon Bonaparte, who led France to preeminence on the European mainland. Nelson’s last and greatest victory against the French was the Battle of Trafalgar, which began after Nelson caught sight of a Franco-Spanish force of 33 ships. Preparing to engage the enemy force on October 21, 1805 Nelson divided his 27 ships into two divisions and signaled a famous message from the flagship HMS Victory: “England expects that every man will do his duty.”

In some hours of fighting, the British devastated the enemy fleet, destroying 19 enemy ships. No British ships were lost, but 1,500 British seamen were killed or wounded in the heavy fighting. The battle raged at its fiercest around the HMS Victory, and a French sniper shot Nelson in the shoulder and chest. The admiral was taken below and died about some minutes before the end of the battle. Nelson’s last words, after being informed that victory was imminent, were “Now I am satisfied. I have done my duty.”

In some hours of fighting, the British devastated the enemy fleet, destroying 19 enemy ships. No British ships were lost, but 1,500 British seamen were killed or wounded in the heavy fighting. The battle raged at its fiercest around the HMS Victory, and a French sniper shot Nelson in the shoulder and chest. The admiral was taken below and died about some minutes before the end of the battle. Nelson’s last words, after being informed that victory was imminent, were “Now I am satisfied. I have done my duty.”

Victory at the Battle of Trafalgar ensured that Napoleon would never invade Britain. Nelson, hailed as the savior of his nation, was given a magnificent funeral in St. Paul’s Cathedral in London. A column was erected to his memory in the newly named Trafalgar Square, and numerous streets were renamed in his honor.

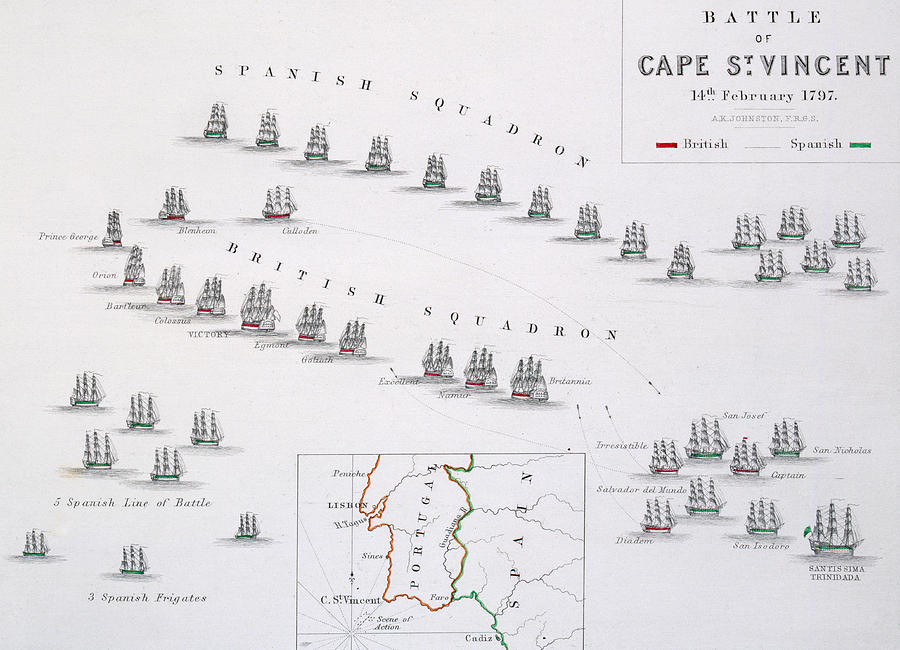

The Battle of Cape St. Vincent took place on February 14, 1797 off the Portuguese coast at Cape St. Vincent. The clash between the British and Spanish fleets was an important battle during the French Napoleonic Wars.

The Battle of Cape St. Vincent took place on February 14, 1797 off the Portuguese coast at Cape St. Vincent. The clash between the British and Spanish fleets was an important battle during the French Napoleonic Wars.

At dawn on February 14, 1797, the British fleet was in attack position. Admiral John Jervis realized that his fleet outnumbered the Spaniards; nearly one-to-two . But it would have been difficult to withdraw at this time. In addition, Jervis knew that a union of the Spanish and French fleets would be even more dangerous. To the advantage of the British, the Spaniards were not yet ready to attack. Their fleet was divided into two groups, while the British ships were already in a line-up order. Jervis decided to drive between the two groups to minimize the enemy fire, while letting him fire in both directions.

They managed this and as the last ship in the British line passed the Spanish, the British line had formed a U shape. At this point the Spanish bore up to make an effort to join their compatriots. Horatio Nelson was at the head of the British fleet on his ship HMS Captain 74, and was closest to the large group of Spanish ships. He came to the conclusion that the commanded maneuver would not allow the British ships to catch up with the Spaniards. Unless the movements of the Spanish ships could be thwarted, everything so far gained would be lost.

As a junior commander, Nelson was subject to the orders of his Commander in Chief (Admiral Jervis on HMS Victory). But he ignored the command, shuffled out of the lineup, and gave orders to take the ship out of line while engaging the smaller group. This group included the Santísima Trinidad, the largest ship afloat at the time and mounting 130 guns, the San José 112, Salvador del Mundo 112, San Nicolás 84, San Ysidro 74 and the Mexicano 112. Nelson’s decision to wear ship was significant.

When Jervis saw the Captain’s maneuver, he ordered his last ship to do the same and the group of British ships prevented the Spanish from grouping together. Nelson drove close to the San Nicolás and ordered his crew to board the enemy ship. Then he ordered to go forward, via the first Spanish ship, to board the second one. Both Spanish vessels were successfully captured. This maneuver was so uncommon and so much admired in the Royal Navy that using one enemy ship to cross to another was soon referred to as “Nelson’s patented bridge for boarding an enemy ship.”

When Jervis saw the Captain’s maneuver, he ordered his last ship to do the same and the group of British ships prevented the Spanish from grouping together. Nelson drove close to the San Nicolás and ordered his crew to board the enemy ship. Then he ordered to go forward, via the first Spanish ship, to board the second one. Both Spanish vessels were successfully captured. This maneuver was so uncommon and so much admired in the Royal Navy that using one enemy ship to cross to another was soon referred to as “Nelson’s patented bridge for boarding an enemy ship.”

Still black with smoke and with his uniform in shreds, Nelson went on board HMS Victory where he was received by Admiral Jervis – “the Admiral embraced me, said he could not sufficiently thank me, and used every kind expression which could not fail to make me happy.” It was a great and welcome victory for the Royal Navy – 15 British ships had defeated a Spanish fleet of 27, and the Spanish ships had a greater number of guns and men. But, Admiral Jervis had trained a highly disciplined force and this was pitted against an inexperienced Spanish navy under Don José Córdoba.

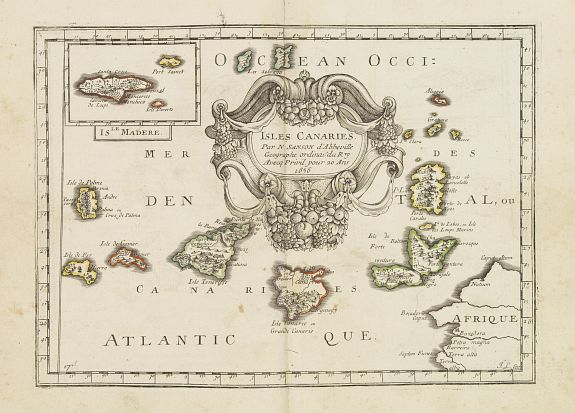

Conquests, battles, traditions, migrations, volcanic eruptions… The history of Tenerife is riddled with highly significant and fascinating events and characters. The Greeks Homer and Hesiod both made mention in their writings of a set of islands located beyond the Gibraltar Strait which they called the Hesperides. They were seen as a heaven on Earth, and this was likely the first reference to the archipelago in ancient times. One of the first reliable records of the Canary Islands was made by Plinius in the 1st century, where he talks of an expedition sent there by Mauritanian King Juba. On the expedition’s return, they brought their king huge dogs as a souvenir of their adventure, which is probably where the archipelago got its name from: Canaries, from canine.

Conquests, battles, traditions, migrations, volcanic eruptions… The history of Tenerife is riddled with highly significant and fascinating events and characters. The Greeks Homer and Hesiod both made mention in their writings of a set of islands located beyond the Gibraltar Strait which they called the Hesperides. They were seen as a heaven on Earth, and this was likely the first reference to the archipelago in ancient times. One of the first reliable records of the Canary Islands was made by Plinius in the 1st century, where he talks of an expedition sent there by Mauritanian King Juba. On the expedition’s return, they brought their king huge dogs as a souvenir of their adventure, which is probably where the archipelago got its name from: Canaries, from canine.

A Spanish military man, conquistador, city founder, and administrator named Adelantado Alonso Fernández de Lugo, began the conquest of Tenerife in 1494 – the most extensive island of the Canary Islands. By then, Tenerife was the only Island that remained unconquered. In 1496, the Island of Tenerife fell under the Castilian Crown. Many of its inhabitants were turned into slaves.

A Spanish military man, conquistador, city founder, and administrator named Adelantado Alonso Fernández de Lugo, began the conquest of Tenerife in 1494 – the most extensive island of the Canary Islands. By then, Tenerife was the only Island that remained unconquered. In 1496, the Island of Tenerife fell under the Castilian Crown. Many of its inhabitants were turned into slaves.

In February 1797 the British defeated a Spanish fleet near Cape St. Vincent by Admiral John Jervis, but failed to strike a solid blow against the Spanish Navy in the uneven struggle. New orders from the Admiralty demanded that he subdue and blockade the Spanish port of Cádiz, where much of the battered Spanish squadron had sought shelter. Jervis’ ships besieged Cádiz but were repelled by unexpected Spanish resistance. An air of mutiny spread over the British crews as their long stay at sea stretched on without results. In April Jervis shifted his gaze to Tenerife upon hearing that Spanish treasure convoys from America arrived regularly at that island. The admiral sent two reconnoitring frigates which surprised and caught two French and Spanish vessels in a night-time raid. Encouraged by this success, Jervis dispatched a small squadron under recently promoted Rear Admiral Horatio Nelson with the aim of seizing Santa Cruz by means of an amphibious attack.

In February 1797 the British defeated a Spanish fleet near Cape St. Vincent by Admiral John Jervis, but failed to strike a solid blow against the Spanish Navy in the uneven struggle. New orders from the Admiralty demanded that he subdue and blockade the Spanish port of Cádiz, where much of the battered Spanish squadron had sought shelter. Jervis’ ships besieged Cádiz but were repelled by unexpected Spanish resistance. An air of mutiny spread over the British crews as their long stay at sea stretched on without results. In April Jervis shifted his gaze to Tenerife upon hearing that Spanish treasure convoys from America arrived regularly at that island. The admiral sent two reconnoitring frigates which surprised and caught two French and Spanish vessels in a night-time raid. Encouraged by this success, Jervis dispatched a small squadron under recently promoted Rear Admiral Horatio Nelson with the aim of seizing Santa Cruz by means of an amphibious attack.

On 14 July Nelson sailed for the Canaries aboard his flagship HMS Theseus (74 guns), leading a squadron composed of HMS Culloden (74 guns), HMS Zealous (74 guns), HMS Seahorse (38 guns), HMS Emerald (36 guns), HMS Terpsichore (32 guns), HMS Leander (50 guns), joined the flotilla. The expedition counted 400 guns and nearly 4,000 men. They arrived in the vicinity of Santa Cruz on 17 July. In Santa Cruz, a hastened reconstruction was carried out to prepare a defence against the British raid. Forts were rebuilt, field works expanded, and the batteries enlarged by doubling their emplacements, with earth sacks piled around.

On 14 July Nelson sailed for the Canaries aboard his flagship HMS Theseus (74 guns), leading a squadron composed of HMS Culloden (74 guns), HMS Zealous (74 guns), HMS Seahorse (38 guns), HMS Emerald (36 guns), HMS Terpsichore (32 guns), HMS Leander (50 guns), joined the flotilla. The expedition counted 400 guns and nearly 4,000 men. They arrived in the vicinity of Santa Cruz on 17 July. In Santa Cruz, a hastened reconstruction was carried out to prepare a defence against the British raid. Forts were rebuilt, field works expanded, and the batteries enlarged by doubling their emplacements, with earth sacks piled around.

22 July 1797 it came to that. The first British attack failed, and Nelson decided to go to the battlefield personally, but the forces of the island were more than ready to fight than he thought. After some days, on 25 July, although some English fighters managed to disembark to the island, they were shot down as they reached the city’s streets, while the cannons fired at the english ships from the shore. Eventually, the English troops were defeated and Horatio Nelson was wounded in his arm; that later amputated. The attack ended with an agreement that allowed the English to return to their ships with their weapons under a promise not to attack any of the islands in the archipelago.

22 July 1797 it came to that. The first British attack failed, and Nelson decided to go to the battlefield personally, but the forces of the island were more than ready to fight than he thought. After some days, on 25 July, although some English fighters managed to disembark to the island, they were shot down as they reached the city’s streets, while the cannons fired at the english ships from the shore. Eventually, the English troops were defeated and Horatio Nelson was wounded in his arm; that later amputated. The attack ended with an agreement that allowed the English to return to their ships with their weapons under a promise not to attack any of the islands in the archipelago.

Nelson would later remark that Tenerife had been the most horrible hell he had ever endured. The Spanish suffered only 30 dead and 40 injured, while the British lost 250 dead and 128 wounded. The journey back to England was difficult, as Nelson had lost many men. Gutiérrez (Spanish general) lent Nelson two ships to help the shot-torn British on their way back. He also allowed the British to leave with their arms and war honours. These acts led to a courteous exchange of letters between Nelson and Gutiérrez. Every year in July, takes place in Santa Cruz de Tenerife the “Recreation Gesta July 25”, in which soldiers, wearing faithful reproductions of uniforms and weapons of the time, recall the victory of Santa Cruz de Tenerife on British troops.

Nelson would later remark that Tenerife had been the most horrible hell he had ever endured. The Spanish suffered only 30 dead and 40 injured, while the British lost 250 dead and 128 wounded. The journey back to England was difficult, as Nelson had lost many men. Gutiérrez (Spanish general) lent Nelson two ships to help the shot-torn British on their way back. He also allowed the British to leave with their arms and war honours. These acts led to a courteous exchange of letters between Nelson and Gutiérrez. Every year in July, takes place in Santa Cruz de Tenerife the “Recreation Gesta July 25”, in which soldiers, wearing faithful reproductions of uniforms and weapons of the time, recall the victory of Santa Cruz de Tenerife on British troops.

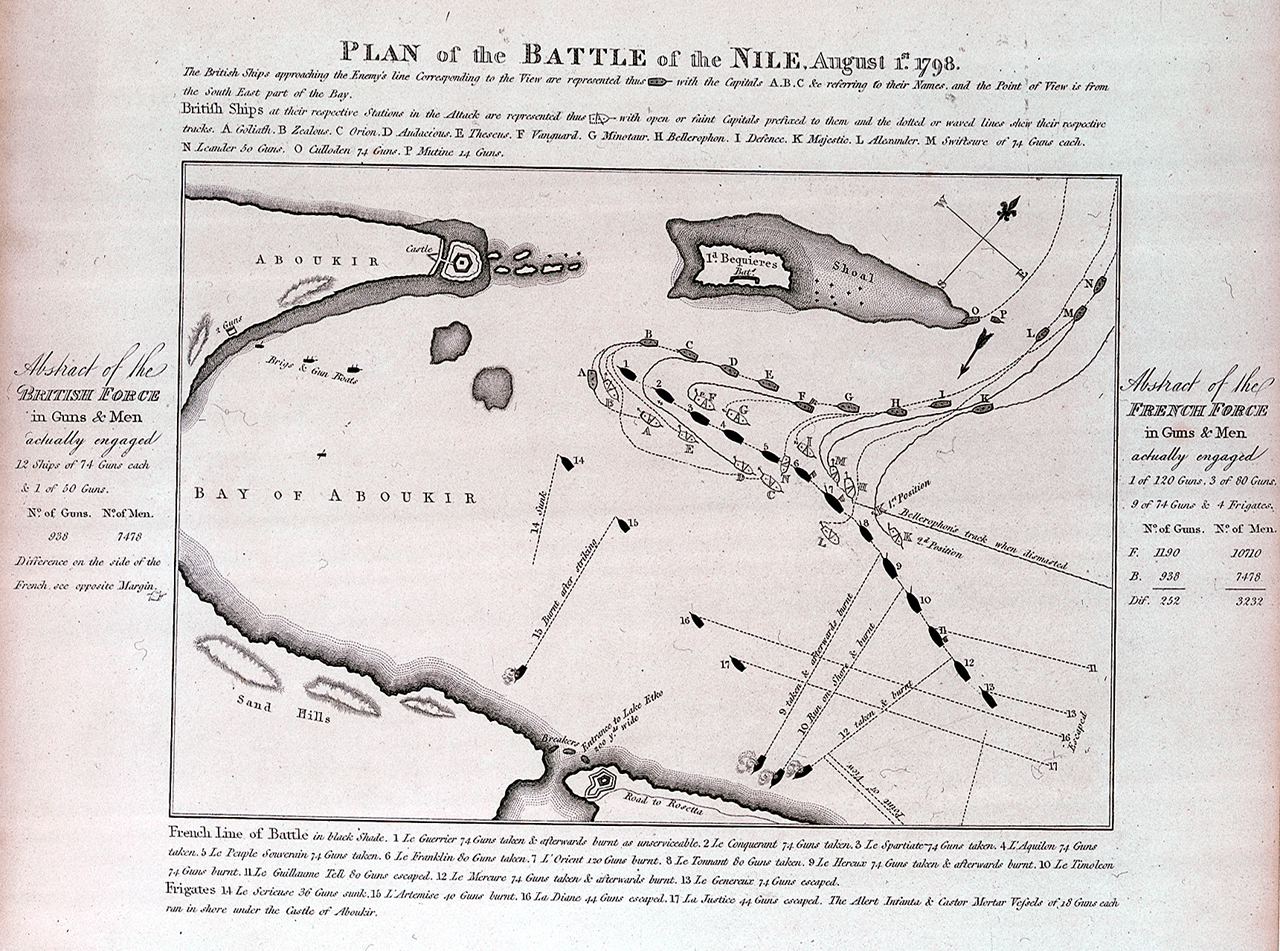

The French Revolutionary general Napoleon Bonaparte in 1798 made plans for an invasion of Egypt in order to constrict Britain’s trade routes and threaten its possession of India. The British government heard that a large French naval expedition was to sail from a French Mediterranean port under the command of Napoleon, and in response it ordered Admiral John Jervis, earl of St. Vincent, the commander in chief of the British fleet, to detach ships under Rear Admiral Sir Horatio Nelson to reconnoitre off Toulon and to watch French naval movements there. Nelson’s flagship, the HMS Vanguard, was dismasted in a storm on May 20, and his group of frigates, now dispersed, returned to the British base at Gibraltar. Meanwhile, Jervis sent Nelson more ships, which joined Nelson on June 7, bringing his strength up to 14 ships of the line.

The French Revolutionary general Napoleon Bonaparte in 1798 made plans for an invasion of Egypt in order to constrict Britain’s trade routes and threaten its possession of India. The British government heard that a large French naval expedition was to sail from a French Mediterranean port under the command of Napoleon, and in response it ordered Admiral John Jervis, earl of St. Vincent, the commander in chief of the British fleet, to detach ships under Rear Admiral Sir Horatio Nelson to reconnoitre off Toulon and to watch French naval movements there. Nelson’s flagship, the HMS Vanguard, was dismasted in a storm on May 20, and his group of frigates, now dispersed, returned to the British base at Gibraltar. Meanwhile, Jervis sent Nelson more ships, which joined Nelson on June 7, bringing his strength up to 14 ships of the line.

The French expedition eluded the British warships and sailed first for Malta, which the French seized early in June. After spending a week at Malta and installing a French garrison at Valletta, Napoleon sailed with his fleet for his main objective, Egypt. Meanwhile, Nelson had found Toulon empty and had correctly guessed the French objective, but, because he lacked frigates for reconnaissance, he missed the French fleet, reached Egypt first, found the port of Alexandria empty, and impetuously returned to Sicily, where his ships were resupplied. Determined to find the French fleet, he sailed to Egypt once more, and on August 1 he sighted the main French fleet of 13 ships of the line and 4 frigates under Admiral François-Paul Brueys d’Aigailliers at anchor in Abū Qīr Bay.

The French expedition eluded the British warships and sailed first for Malta, which the French seized early in June. After spending a week at Malta and installing a French garrison at Valletta, Napoleon sailed with his fleet for his main objective, Egypt. Meanwhile, Nelson had found Toulon empty and had correctly guessed the French objective, but, because he lacked frigates for reconnaissance, he missed the French fleet, reached Egypt first, found the port of Alexandria empty, and impetuously returned to Sicily, where his ships were resupplied. Determined to find the French fleet, he sailed to Egypt once more, and on August 1 he sighted the main French fleet of 13 ships of the line and 4 frigates under Admiral François-Paul Brueys d’Aigailliers at anchor in Abū Qīr Bay.

1 August 1798, although there were a few hours left until nightfall and Brueys’s ships were in a strong defensive position, being securely ranged in a sandy bay that was flanked on one side by a coastal artillery on Abū Qīr Island, Nelson gave orders to attack at once. Several of the British warships were able to maneuver around the head of the French line of battle and thus got inside and behind their position. Fierce fighting ensued, during which Nelson himself was wounded in the head. The climax came at night, when Brueys’s 120-gun flagship, L’Orient, which was by far the largest ship in the bay, blew up with most of the ship’s company, including the admiral. The fighting continued for the rest of the night; just two of Brueys’s ships of the line and a pair of French frigates escaped destruction or capture by the British. The British suffered about 900 casualties, the French about 10 times as many.

1 August 1798, although there were a few hours left until nightfall and Brueys’s ships were in a strong defensive position, being securely ranged in a sandy bay that was flanked on one side by a coastal artillery on Abū Qīr Island, Nelson gave orders to attack at once. Several of the British warships were able to maneuver around the head of the French line of battle and thus got inside and behind their position. Fierce fighting ensued, during which Nelson himself was wounded in the head. The climax came at night, when Brueys’s 120-gun flagship, L’Orient, which was by far the largest ship in the bay, blew up with most of the ship’s company, including the admiral. The fighting continued for the rest of the night; just two of Brueys’s ships of the line and a pair of French frigates escaped destruction or capture by the British. The British suffered about 900 casualties, the French about 10 times as many.

The Battle of the Nile had several important effects. It isolated Napoleon’s army in Egypt, thus ensuring its ultimate disintegration. It ensured that in due time Malta would be retaken from the French, and it both heightened British prestige and secured British control of the Mediterranean.

The Peninsula was a military conflict between France and Spain and its allies over the control of the Iberian Peninsula during the Napoleonic wars. The war began when the united Spain and France in 1807 succeeded in conquering Portugal. A year later, the French invaded their long-standing ally, Spain. The war continued until 1814, when the sixth coalition forces managed to defeat Napoleon. In Spain, the war is known as the Spanish Independence War.

The Peninsula was a military conflict between France and Spain and its allies over the control of the Iberian Peninsula during the Napoleonic wars. The war began when the united Spain and France in 1807 succeeded in conquering Portugal. A year later, the French invaded their long-standing ally, Spain. The war continued until 1814, when the sixth coalition forces managed to defeat Napoleon. In Spain, the war is known as the Spanish Independence War.

This war is one of the first widespread guerrilla wars and the first national wars in Europe. At first, the French defeated Spain. The British and Portuguese armies have been able to liberate Portugal from French domination and make it a safe place for their next troops. The war was heavily bloody, and the annual revolt of the Spanish states was also a threat to the French central government, which was in Madrid.

Several years of war in Spain destroyed the great Napoleonic army. Despite repeated victories of the French in the battle against the Spanish guerrillas, their storage and power were in decline. It was gradually clear that Napoleon’s attack on Spain was a huge and irreparable mistake.

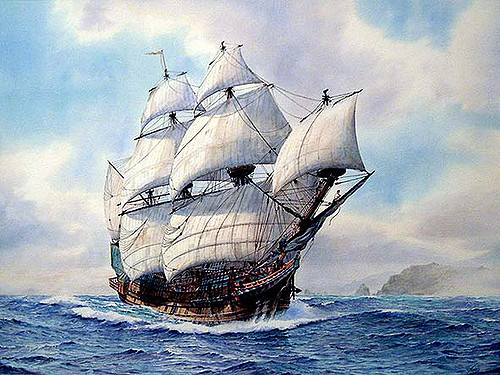

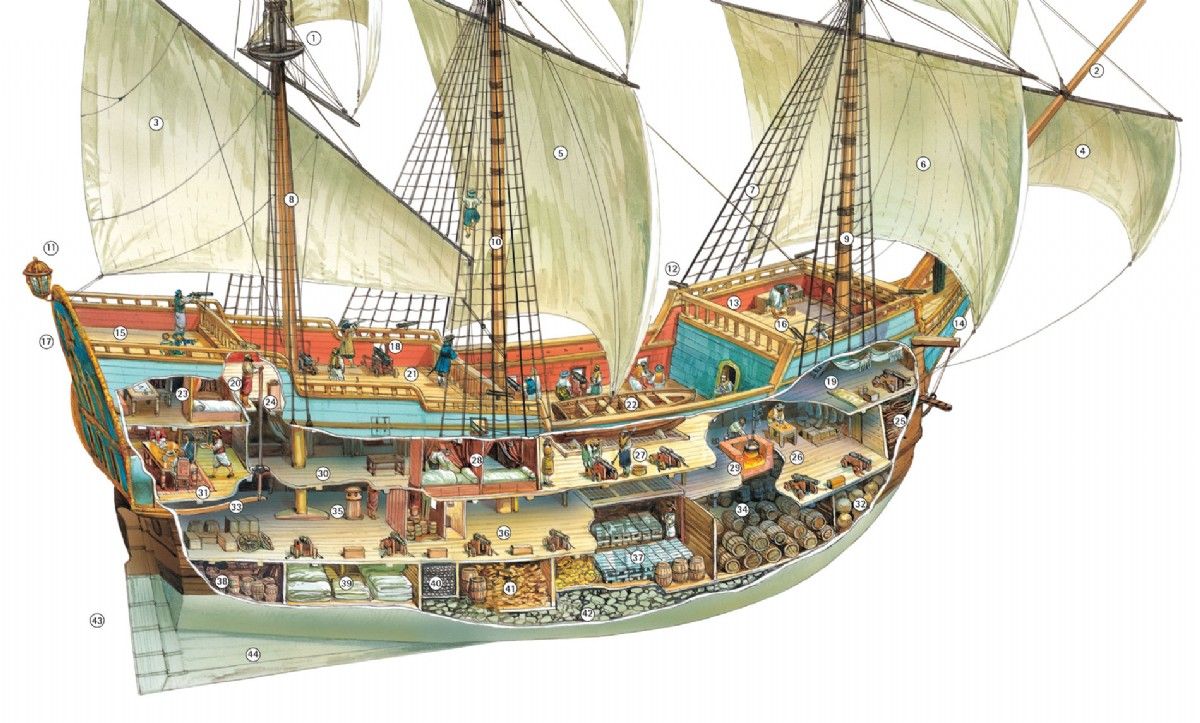

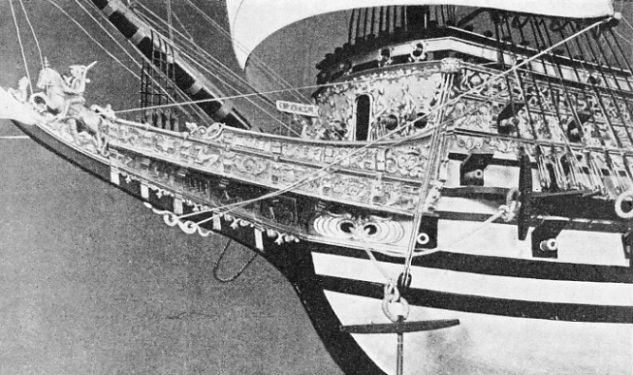

The Galleon developed in the early 16th century from ships such as the caravel and the carrack. The galleon design varied between regions. The shipwright varied hull and sail configuration based on the ship’s homeport, its destination, and the cargo it carried. Galleons were also fitted as warships and tended to have more ribs and bracing to withstand gunfire.

The Galleon developed in the early 16th century from ships such as the caravel and the carrack. The galleon design varied between regions. The shipwright varied hull and sail configuration based on the ship’s homeport, its destination, and the cargo it carried. Galleons were also fitted as warships and tended to have more ribs and bracing to withstand gunfire.

The caravel was like sailing a bathtub, so the hull of the galleon was elongated for stability, and the forecastle was lowered, creating less wind resistance that helped increase the speed of the ship and its ability to maneuver. The galleon usually carried three masts, and the fore and main masts were square rigged, with the mizzenmast being lateen rigged. The forecastle was lower than the aft castle, housed the crew’s toilets (head), which would drop refuse straight into the sea.

The caravel was like sailing a bathtub, so the hull of the galleon was elongated for stability, and the forecastle was lowered, creating less wind resistance that helped increase the speed of the ship and its ability to maneuver. The galleon usually carried three masts, and the fore and main masts were square rigged, with the mizzenmast being lateen rigged. The forecastle was lower than the aft castle, housed the crew’s toilets (head), which would drop refuse straight into the sea.

Below the bowsprit was a “beak” used for ramming. The beakhead would be one of the most ornate sections of a ship, particularly in the extravagant Baroque-style ships of the 17th century. The sides were often decorated with carved statues and located directly underneath was the figurehead, usually in the form of animals, shields or mythological creatures.

Below the bowsprit was a “beak” used for ramming. The beakhead would be one of the most ornate sections of a ship, particularly in the extravagant Baroque-style ships of the 17th century. The sides were often decorated with carved statues and located directly underneath was the figurehead, usually in the form of animals, shields or mythological creatures.

Many European countries used galleons as merchant or supply ships in peace, and could quickly convert them to war ships in times of trouble. The Spanish used the vast amount of cargo space in the Galleon to carry the New World treasure across the Atlantic and also for his Armada. The galleon could withstand the rigors of ocean voyages. An example of the most epic Galleons can be San Francisco, San Jose, and especially Santa Maria, which led Christopher Columbus Caravel and traveled to the unknown lands of the Atlantic Ocean.

Many European countries used galleons as merchant or supply ships in peace, and could quickly convert them to war ships in times of trouble. The Spanish used the vast amount of cargo space in the Galleon to carry the New World treasure across the Atlantic and also for his Armada. The galleon could withstand the rigors of ocean voyages. An example of the most epic Galleons can be San Francisco, San Jose, and especially Santa Maria, which led Christopher Columbus Caravel and traveled to the unknown lands of the Atlantic Ocean.

The Spanish Navy (Spanish: Armada Española) is the maritime branch of the Spanish Armed Forces and one of the oldest active naval forces in the world. It was an enormous 130-ship naval fleet – mostly Galleons, dispatched by Spain in 1588 as part of a planned invasion of England. Following years of hostilities between Spain and England, King Philip II of Spain assembled the flotilla in the hope of removing Protestant Queen Elizabeth I from the throne and restoring the Roman Catholic faith in England.

The Spanish Navy (Spanish: Armada Española) is the maritime branch of the Spanish Armed Forces and one of the oldest active naval forces in the world. It was an enormous 130-ship naval fleet – mostly Galleons, dispatched by Spain in 1588 as part of a planned invasion of England. Following years of hostilities between Spain and England, King Philip II of Spain assembled the flotilla in the hope of removing Protestant Queen Elizabeth I from the throne and restoring the Roman Catholic faith in England.

Spain’s “Invincible Armada” set sail that May and met for the first time the English fleet on end of July. The British had already come forward for confrontation and kept their distance and bombard the Spanish flotilla with their heavy naval cannons. The Spaniards resisted for more than a week. The English was outfoxed and at a midnight set eight empty vessels ablaze and allowed the wind and tide to carry them toward the Spanish fleet hunkered at Calais Roads. The sudden arrival of the fireships caused a wave of panic to descend over the Armada. Several vessels cut their anchors to avoid catching fire, and the entire fleet was forced to flee to the open sea. With the Armada out of formation, the English initiated a naval offensive in what became known as the Battle of Gravelines.

The Royal Navy inched perilously close to the Spanish fleet and unleashed repeated salvos of cannon fire. Shortly after the Battle of Gravelines, a strong wind carried the Armada into the North Sea, dashing the Spaniards’ last hopes. With supplies running low and disease beginning to spread through the fleet, they resolved to abandon the invasion mission and return to Spain, but its journey home proved to be far more deadly. The once-mighty flotilla was ravaged by sea storms as it rounded Scotland and the western coast of Ireland. Several ships sank in the squalls, while others ran aground or broke apart after being thrown against the shore. By the time the “Great and Most Fortunate Navy” finally reached Spain two months later, it had lost as many as 60 of its 130 ships and suffered some 15,000 deaths.

The Royal Navy inched perilously close to the Spanish fleet and unleashed repeated salvos of cannon fire. Shortly after the Battle of Gravelines, a strong wind carried the Armada into the North Sea, dashing the Spaniards’ last hopes. With supplies running low and disease beginning to spread through the fleet, they resolved to abandon the invasion mission and return to Spain, but its journey home proved to be far more deadly. The once-mighty flotilla was ravaged by sea storms as it rounded Scotland and the western coast of Ireland. Several ships sank in the squalls, while others ran aground or broke apart after being thrown against the shore. By the time the “Great and Most Fortunate Navy” finally reached Spain two months later, it had lost as many as 60 of its 130 ships and suffered some 15,000 deaths.

The vast majority of the Spanish Armada’s losses were caused by disease and foul weather, but its defeat was nevertheless a triumphant military victory for England. While the Spanish Armada is now remembered as one of history’s great military blunders, it didn’t mark the end of the conflict between England and Spain. In 1589, Queen Elizabeth I launched a failed “English Armada” against Spain. King Philip II, meanwhile, later rebuilt his fleet and dispatched two more Spanish Armadas in the 1590s, both of which were scattered by storms. It wasn’t until 1604—over 16 years after the original Spanish Armada set sail—that a peace treaty was finally signed ending the Anglo-Spanish War as a stalemate.

The vast majority of the Spanish Armada’s losses were caused by disease and foul weather, but its defeat was nevertheless a triumphant military victory for England. While the Spanish Armada is now remembered as one of history’s great military blunders, it didn’t mark the end of the conflict between England and Spain. In 1589, Queen Elizabeth I launched a failed “English Armada” against Spain. King Philip II, meanwhile, later rebuilt his fleet and dispatched two more Spanish Armadas in the 1590s, both of which were scattered by storms. It wasn’t until 1604—over 16 years after the original Spanish Armada set sail—that a peace treaty was finally signed ending the Anglo-Spanish War as a stalemate.

Nowadays, armada is generally referred to as a naval force or the navy of a Spanish- or Portuguese-speaking country. The term means in Spanish and Portuguese “navy” or “naval force”. It is used as a general term for domestic or foreign navies (eg, Armada de México: Mexican navy, Armada romana: Roman navy).